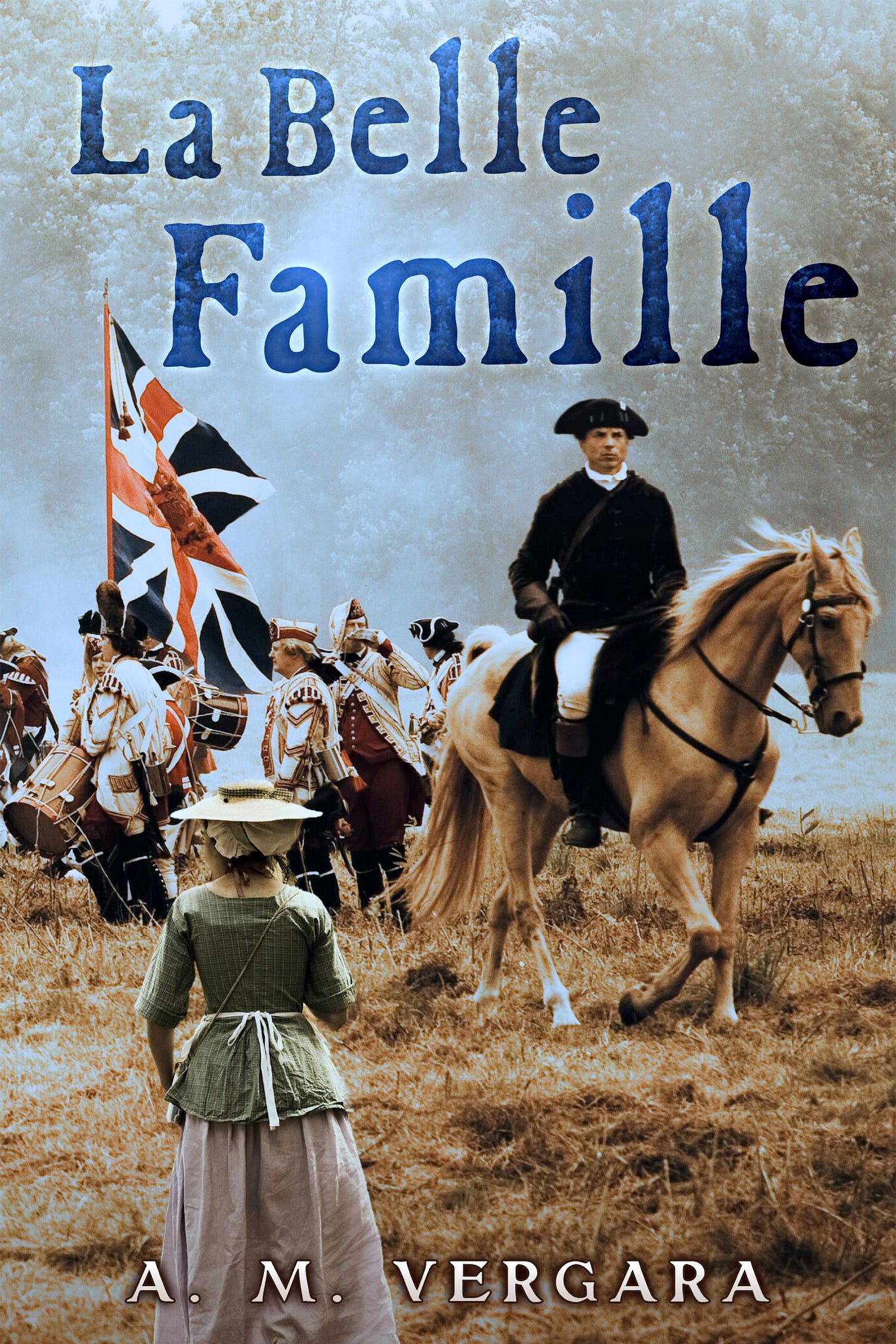

Announcing LA BELLE FAMILLE

Dear Readers,

In the midst of a very eventful summer, I am so pleased to announce the release of La Belle Famille (unrelated to my first book, Firefax). Today is the 265th anniversary of the Battle of La Belle-Famille, July 24th, 1759, so it seemed a fitting day to release the work.

This novel follows three characters through the events of July 1759, in the midst of the French and Indian War, building up to a little-known, but extremely pivotal battle. Adam is a French Marine struggling to reconcile himself to the horrors of war and the part he plays in them. Lidia is a determined, fierce, angry young woman, a survivor of a particularly heinous assault on a peaceful village of Palatine German settlers. Finally, you will meet Sofie, a stubborn, strong, peace-loving mother who takes a terrible risk to warn the British of impending reinforcements.

This is a tale of courage, survival, and family caught up in the evils of war. Below you can read an excerpt. If you like what you’ve read and want to see more, please consider purchasing the book wherever you typically buy books. Any reviews are so deeply appreciated. I hope you enjoy the story and look forward to sharing the sequel to Firefax with you in the not too distant future . . .

You can find La Belle Famille where ever books are sold, but here are few links to get you started:

EXCERPT FROM LA BELLE FAMILLE:

It was useless. Stupid. Hopeless. Sofie knew she could not make it. She had been running for miles with a steady, shuffling gait she had learned among the Haudenosaunee. If she kept jogging at this pace, she could go on for many hours. She stayed off the overgrown portage road, keeping close to the river. She had lightened her load as well, to almost nothing. The first thing she had jettisoned from the few belongings she still had was Will’s musket. Dropping it made her feel as if she had lost a thousand pounds at once; it made her feel faster.

She tried to hide her tracks, running through streams for as long as they lasted, swinging on low hanging vines, and following meandering deer trails. But she knew the grass and the earth would show the marks her passing made to any Indian tracker with an ounce of skill. Her mad ride and now wild, desperate run to the fort would be for naught.

About midday she found a stony ravine—the first bit of luck she had encountered since she heard her pursuers. She let hope surge anew at the sight of the bare rock—bare rock that would show no prints. She kept to the stones for as long as she could, more than a mile, enough perhaps to throw the trackers off her trail, at least temporarily. They would follow the ravine and look for the place her prints went back into the forest; it would slow them. But she did not let her rising spirits at this stroke of good fortune overwhelm her sense of reality. She knew the trackers were not far behind, and even at her slow, jogging gait, she could not go on forever. She was exhausted. She had already ridden hard with barely any sleep for days, she was carrying a sick infant that still had sufficient strength to whimper for food, and her breasts ached, heavy with milk. She was spent. Every time she paused, even for only a second to catch her breath, every time she even entertained the idea of feeding the infant, she thought she heard the sound of her pursuers. Horses—they had horses. They could overtake her easily on the flat, though in the thick, tangled closeness of the forest she had a slight advantage.

She pushed herself through snarls of poison ivy growing in vines as big around as her arm, through brambles that tore at her breeches, and clambered over rocks that pierced her shoes. There were dense copses of pine, with low branches that raked her skin, and places in the wood so tangled with bracken that she stumbled and tripped with every step. She passed through groves of ash, oak, and maple that grew so thick that she practically had to crawl to slide beneath their overhanging lower limbs, taking care not to let the branches tear her child from his cradleboard.

The fear of the pursuit was a distraction from her infant’s health. She knew he was alive; sometimes he moved, sometimes he let out a faint yelp. She had been running since the battle with the mountain lion. She had not had even a second to take the cradleboard off, and she did not know if he was improved, the same, or worse than he had been. The terrible knowledge that this adventure would kill her child oppressed her, slowing her run with stifling, overwhelming despair, a far heavier burden than Will’s musket had been.

At last she burst out of the trees and found herself upon a rocky cliff, a bluff, overlooking a vast expanse of forest. The foliage of the treetops spread like an impenetrable floor below her, far below. To her left she could hear the powerful roar of Niagara Falls, still out of sight. She drew in a gasping breath, her heart hammering in her ears, panting, exhausted. Frantically, she scanned the steep rocks for a way to climb down. The child on her back let out a pathetic, feeble cry and Sofie sank to her knees, then onto her hands, sobbing and shaking and retching.

Her strength gradually returned and she removed the cradleboard from her back. The child did not look better, but neither did he look worse. His eyes were still bleary, his rash red and scaly, but, to her relief, he took her nipple. Both breasts had begun to leak earlier in the run, soaking her shirt and waistcoat with milk. The baby ate greedily, enough to loosen the tension in her chest, and then he fell asleep. Briefly she again entertained the idea that he would live, that he was going to survive. Then the memories of the Others came rushing back, the haunting faces of the babies, the haunting face of little Martin. The infant would die, and she would be the one who had killed him, killed him to save his father, as if his life mattered less.

From this dark reverie, crouched over her child upon the precipice, she looked up, catching sight in the distance of a rising cloud of vapor. The falls, the mighty falls. She remembered breathlessly the first time she had journeyed to Niagara Falls with her Will, how he had watched with laughter and pride in his eyes while she sobbed on her knees, whispering prayers and hymns to heaven at the awesome glory of the endless water. There had been immeasurable tons of water, thousands and thousands of tons, pouring from above, weight enough to crush an entire village, weight enough to crush the world, and beauty enough to drive the hardest, coldest soul to their knees. A mist settled upon her eyes at the precious memory: how she had not been able to stand or look away for hours, and how hard she had prayed, and the feeling of Will’s strong arms wrapped around her as she wept.

“If I can just get you to him before you die . . . ,” she whispered aloud, looking down at the infant with the faintest hint of red in his thin golden hair. “You would love him, Eodi’nigoiyo-ak. You would love him so much, and he would love you.”

Sofie looked up again, as the sun began to set beyond the waterfall, orange light spilling from the horizon, piercing and brilliant, casting a glorious aureate mantle over the world and softening the edges of the wilderness. The orange beams of light turned to pink and amber waves in the purpling clouds. Involuntarily she began singing softly. As she sang she put the child back in his cradleboard. He opened his eyes again, gazing up at her solemnly, as if he knew the meaning of the words.

“Und wenn die Welt voll Teufel wär’

und wollt’ uns gar verschlingen,

so fürchten wir uns nicht so sehr,

es soll uns doch gelingen.

“Der Fürst dieser Welt,

wie sau”r er sich stellt,

tut er uns doch nicht;

das macht, er ist gericht’t;

ein Wörtlein kann ihn fällen.”

Something moved in the corner of her vision and she stopped singing, turning just as two French troopers and two Indian scouts emerged onto the grassy bluff where she stood. They paused, staring at her, as if trying to make sense of what they were seeing. She almost smiled as she glanced down at the spectacle she had become: a woman in the middle of nowhere, perched on a precipice, the sun setting behind her, dressed in men’s clothing, her shirt stiffened from dried milk, her breasts exposed, her golden hair matted, and a swaddled infant lying in a cradleboard at her feet. The troopers started toward her. There was no time. No time to think, no time to find a weapon, no time to negotiate. There was no time for anything. Sofie yanked the cradleboard onto her back and turned toward the cliff just as the men broke into a run, shouting in French at her.

“Arrête-toi! Halte! Ne saute pas!”

But Sofie wasn’t listening. She glanced down for only a second at the dizzying distance to the ground and then swung her legs over the edge, determined to make the harrowing descent if it was the last thing she ever did. One of the soldiers darted forward, grabbing at her. He caught the wampum belt wrapped around her waist, holding her for a second as she yanked away. The belt tore and beads flew in every direction, and then she was falling.